A historical analysis of America’s two-party system.

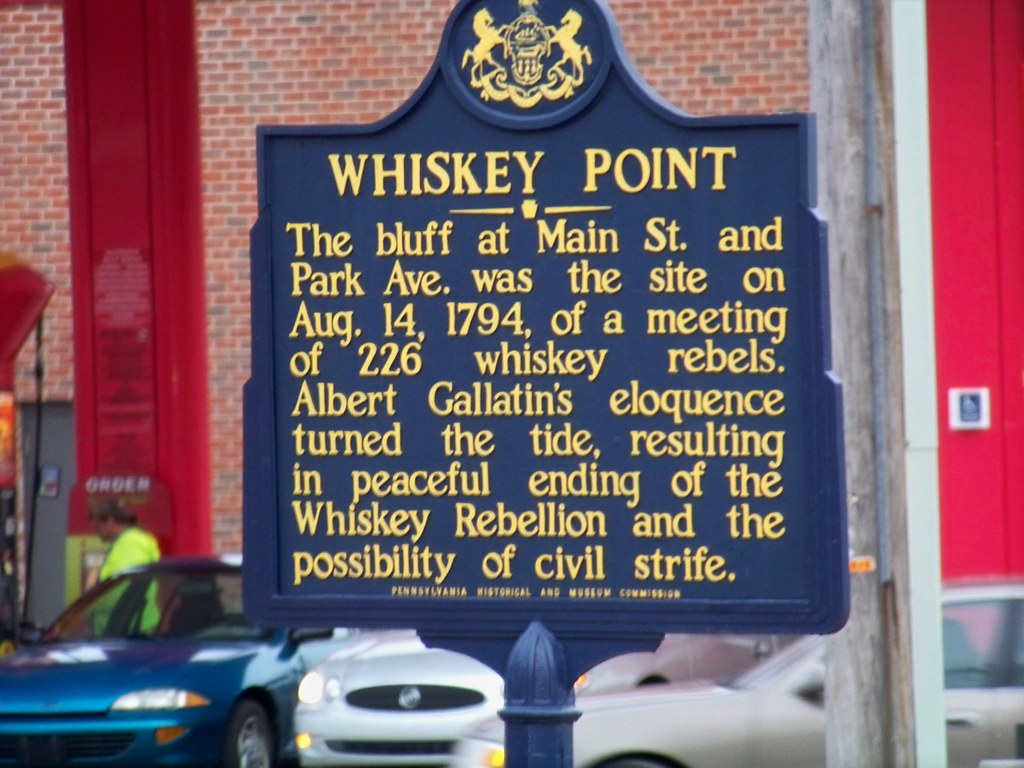

Plaque in Pennsylvania recognizing the site of the Whiskey Rebellion. / Photo credit: Flickr.

By Nicolas Scola

Find yourself frustrated with our current choice of presidential candidates for the 2024 election? What if I told you that our democratic system was never intended to function this way?

In his Farewell Address George Washington cautioned our fledgling country to avoid political factions and foreign entanglements… quite a nice sentiment that was quickly tossed into the Schuylkill or whatever body of water the founding fathers used to dump their waste during their short stay in the City of Brotherly Love.

The America of 2024 is starkly different from the country that Washington said goodbye to in 1796. Modern America now stands at the epicenter of the world as a hegemon, extending its reach to the far corners of the earth. Regarding Washington’s advice about political factions… an elephant or donkey could probably conclude that we failed dramatically. But why do we have political parties in the first place? Were they the well-intentioned result of years of deliberation? No, like most of the best things that occur in life, they were the by-product of spontaneity with a little pinch of human nature. Enter whiskey.

Taxes! You either hate them or you really hate them. Regardless, any introductory level public policy course stresses one thing: if the government wants to raise revenue, tax something where demand or supply is relatively inelastic (a good that people will buy or sell regardless of the costs). Whiskey, as one of the most addictive alcoholic beverages, is the perfect example of a taxable item that could line Uncle Sam’s pockets with gold. Instead, the whiskey excise tax filled Western Pennsylvania skies with copious amounts of gunpowder. Modest farmers were enraged by this new form of taxation. Unable to simultaneously pay the tax and make a profit, and frustrated by tensions with Native Americans on the frontier, they took up arms against the tax collectors. However, the United States army eventually arrived in Western Pennsylvania led by George Washington, the first and only sitting president to lead troops into battle while in office. With speed and precision, America’s most notorious founding father was ultimately victorious.

But that is not the end of the story. Aside from being a tense moment of national uncertainty in United States history, it also created a game that everyone loves but few know how to play: politics. Yes, the Whiskey Rebellion, a footnote in history that few have heard about, is responsible for Congress rarely getting anything done. While disagreements and dissent have been a hallmark of the American experiment, boldly emerging during the Constitutional Convention, the creation of political parties did not formally occur until the early 1790s. The Whiskey Rebellion (1794) echoed a broader dichotomy of interests that caused friction between the early founding fathers and sharpened the divide between America’s nascent political factions. Questions such as: “Was the federal government constitutionally permitted to tax a good such as whiskey?” drew starkly different answers. As we know from the political landscape today, whenever there are two sides to an argument, dispute is almost a given. Federalists, aligned with President Washington, favored a strong central government and therefore championed Congress’ authority to broadly tax. Conversely, Anti-Federalists (later Democratic-Republicans), led by Thomas Jefferson, promoted the interests of the states and favored a more constrained federal government. Even before the ink had dried on President Washinton’s Farewell Address, the seeds of American factionalism were already beginning to germinate.

With a little taste of the history, you may be captivated by the overwhelming thought that political parties are useless and should be summarily destroyed. Conversely, it is equally likely that you are completely infatuated with political parties: you only watch news that caters to your political beliefs, you vote for candidates within your party 95% of the time, and you have a pin of your party’s emblem that you proudly wear to cocktail parties. In reality, separating into groups is a dynamic function of voting. It spurs innovation and forces politicians to adapt to societal norms in order to maintain popularity.

While it is important to recognize that in the aftermath of the Revolutionary War, George Washington and the founding fathers never intended to split into Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, Democrats and Whigs, Democrats and Republicans, and even Bull Moose and Socialists, the current system of political faction in modern America is a necessary evil. Competition is the basis of change in a free market economy. The externalities of uni-party rule are clearly noted. Taking Communist Cuba as a case study, it is clear that there is a strong correlation between lack of political competition and subversion of freedom. For example, after rounds of protests in 2021 and 2022 over a stagnant economy and crumbling infrastructure, hundreds of Cubans were arrested, facing trials that violated basic guarantees of due process. Furthermore, in May 2022, Cuban President Miguel Dìaz-Canel Bermúdez passed a new penal code, placing broad sanctions on demonstrations and dissent. Without another political party to challenge Diaz-Canel and the Communist Party of Cuba, suppression has prevailed.

Basic human nature aptly displays that lacking an incentive to innovate, the status quo reigns supreme. Without at least two political parties, office-motivated politicians would have little reason to take new stances on issues, paving the way for collusion and corruption. This is not to say America’s two-party system is the most efficient mode of social choice in the world or that political parties are unimpeachable. Instead, it is a reflection of the realities of human behavior. As James Madison understood: “ambition must be made to counteract ambition.”

Sadly, absent a panacea which can divest humans of their innate zeal to compete, a utopia without political parties is entirely impractical. Instead of attempting to change the current system, if you find yourself frustrated by political parties, just do the noble thing and blame whiskey!

Nicolas Scola is a freshman in the College studying Philosophy, Politics, and Economics from Morristown, NJ. Nicolas is also the podcast director for The Pennsylvania Post. His email is nscola@sas.upenn.edu.