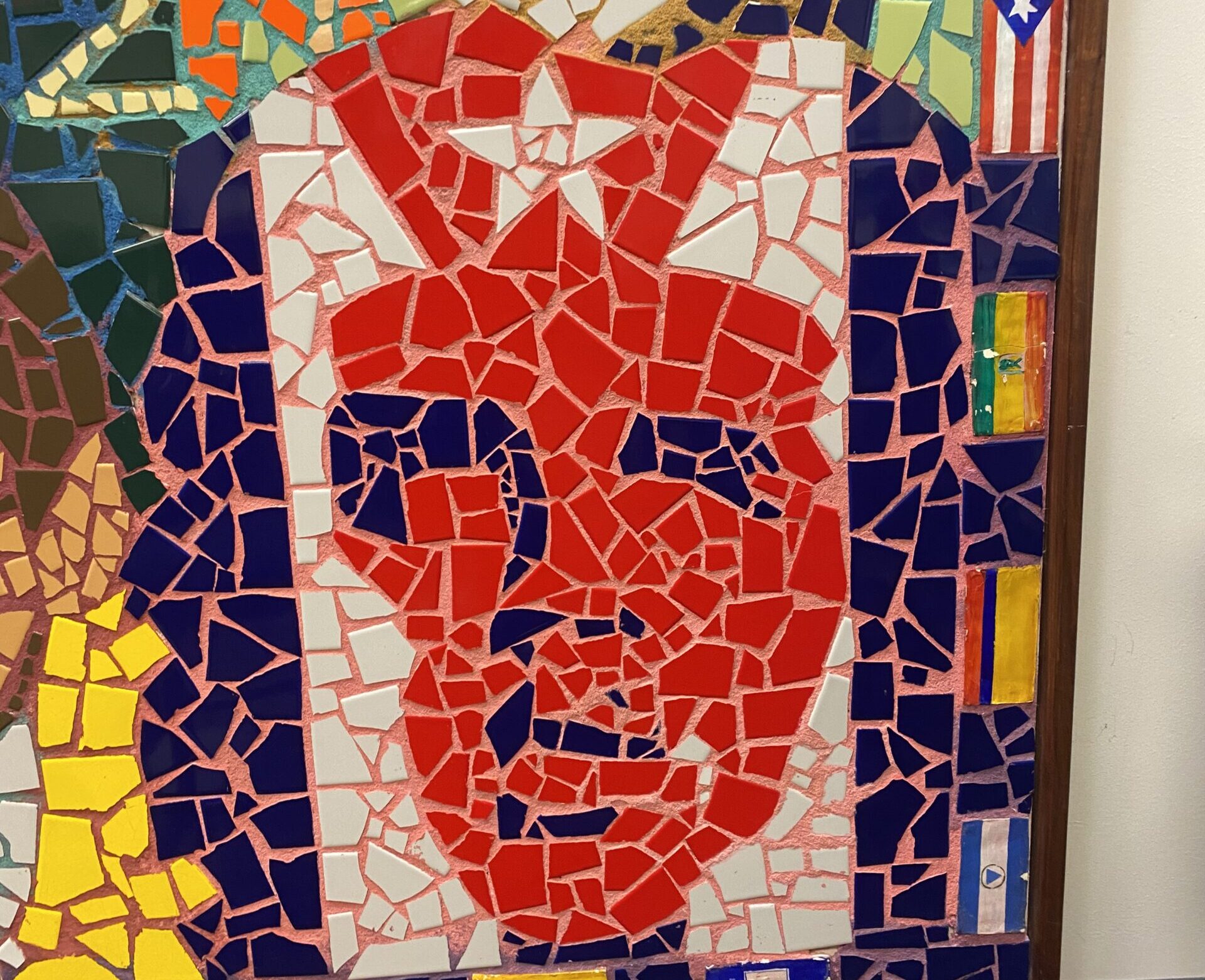

A vivid reminder of oppression, the mural at La Casa Latina fuels an ongoing struggle for recognition and respect among Cuban students.

Photo Credit: Jennifer Mesa

By Jennifer Mesa

Editor’s Note: This piece is part of a series. As the second part of this series, we have already released a timeline of events that outline the movement to remove this mural since its establishment in 2001. We plan to continue to release pieces that highlight Cuban students’ voices, experiences, opinions, and news on the mural conflict as it continues to unfold today. If you have any additional ideas about aspects of this conflict, you would like to better understand, or if you have responses, please email jenmesa@sas.upenn.edu. Be sure to sign up for our newsletter to be the first to hear when we release the next part.

As a Cuban student at Penn, it is both exhausting and disheartening to see this conflict drag on for 23 years, despite continuous efforts by Cuban students to address the issue. For an institution that prides itself on being a “safe space” for people of all backgrounds, the university’s ongoing neglect toward the Cuban student body by denying our requests is astonishing. Time and again, Cuban students have expressed discomfort over the mural at La Casa Latina, the space supposedly designed for their wellbeing and community. Instead, Penn has maintained an image of a man, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, responsible for the deaths of thousands of Cubans, embedded into the Cuban flag itself — the very symbol of our nation.

For many Cuban students, La Casa, a place meant to foster connection among Latin American students, has become a space of exclusion and discomfort. How is it that a place intended for healing and cultural celebration upholds the image of a man responsible for the destruction of Cuba? This neglect perpetuates the alienation of Cuban students who feel their voices are systematically ignored, despite their consistent and reasonable demands.

One of the recurring obstacles to progress has been the presence of sympathizers of Che’s movement among the non-Cuban Latin student body and administration. Additionally, staff at La Casa often mask their reluctance to act by insisting on “getting the full story,” despite repeated attempts by Cuban students to explain the trauma caused by Che’s actions. There have been countless empty promises from the administration, and the result has been a mural that continues to glorify a murderer while ignoring the pain of the Cuban students whose families suffered under his regime.

Let’s be clear: Che Guevara was objectively a monster, and a sadistic killer who embodied pure evil. Those who sympathize with his communist ideals, no matter how misguided, cannot and should not excuse the bloodshed, terror, and oppression he unleashed. He was not only a murderer but a racist, homophobic tyrant who reveled in the suffering of others. Guevara brought death and devastation to thousands of innocent Cubans, leaving a legacy of brutality and fear that still grips the nation to this day. His so-called “revolutionary justice” was nothing more than a bloodthirsty campaign of executions, torture, and forced labor camps, where dissidents were crushed under the weight of his barbarism. Che Guevara is an irredeemable scum of the earth whose cruelty has forever scarred Cuba and the world. He should be condemned to the darkest depths of history, not commemorated with an honorary art installation in a space where Cuban students should feel welcomed.

During the Cuban Revolution, Che Guevara was responsible for the deaths of thousands. While the exact number of his victims remains unknown, Guevara openly admitted to ordering countless executions—none of which provided the victims with any semblance of due process. One of many recovered lists of victims directly executed by El Che between 1957 and 1959, for example, lists 216 names. These people were not criminals but anyone Guevara deemed a “deviant” or an enemy of his revolutionary ideals, making them targets for his ruthless brand of “justice.”

As the commander of La Cabaña fortress and founder of the Guanahacabibes camp, forced labor camps, Che himself directly participated in the execution of at least 176 people without trial. His “revolutionary justice” involved purging dissidents, traitors, and anyone who opposed the revolution, including many who were executed without due process. These forced labor camps targeted those he deemed unfit — gay men, religious figures, and others labeled “counter-revolutionary”. Amongst these people he deemed unfit are Afro-Cubans and anyone of the Black race. In his diary, he repeatedly refers to Black people as being unclean, lazy, and inherently inferior to White people.

The camps, were estimated to have held tens of thousands of people who were subjected to unspeakable torture and brutality. This “revolutionary justice” model Che brought to Cuba played a key role in inspiring and building Military Units to Aid Production or UMAPs (Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción). These were also forced labor camps that were used to “re-educate” anyone considered deviant from revolutionary ideals. Over 30,000 internees were subjected to unspeakable abuses, with hundreds reportedly committing suicide, killed through torture, psychologically tortured, and countless executed. A 1967 human rights report from the Organization of American States reported the horrific conditions: inmates worked 10-12 hours a day under inhumane circumstances, with inadequate food, unclean water, and unsanitary living quarters. The UMAP camps similarly targeted Afro-Cubans, homosexuals, religious individuals, or anyone who dared to speak freely and expressed distaste towards the dictatorship. The UMAP camps played a pivotal role in institutionalizing fear and repression in Cuba– intense policing arose around Cuba, threatening Cubans that any act deemed to be anti-revolutionary (which was largely up to the interpretation of the police officers). Still to this day, citizens live under the constant threat of persecution for dissenting against the regime—many simply “disappear.” For this enduring nightmare, we can thank Che.

Beyond his direct role in the mass murder of innocents, Che Guevara played a pivotal part in establishing the brutal regime that still holds Cuba hostage. This isn’t just a chapter of history—it’s a living nightmare that a majority of my own family still endures. They face starvation, lack of medical care, and daily fear under a government that crushes free speech and punishes anyone brave enough to question it. Cuba has become the top migrant-sending nations as a result of the unlivable condition Che and his comrades left Cuba in. Che Guevara’s legacy is one of death, oppression, and suffering—driving thousands of Cubans, including my family, to risk everything to flee from a country once beautiful but now ruined.

Despite these horrors, Che Guevara is glorified as a hero of social justice in classrooms and academic spaces across the world, including here at Penn. Often, course material celebrates him while his atrocities and blatant human rights violations are conveniently ignored. Worse, thanks to this mural, even in La Casa Latina, I find no refuge, as I’m confronted by the image of this despicable man—a murderer of my people—proudly displayed on embedded into the very fabric of our flag, which should be a symbol of perseverance and the fight for freedom against tyrants like Che.

Given the clear atrocities Che is directly responsible for, it is astonishing that over the last 23 years Cuban students are repeatedly forced to justify their position, met with opposition, and dismissed in their efforts to remove this evil figure from their very own flag. It is deeply hypocritical, especially when considering the ease with which other student groups at Penn have succeeded in removing paintings or statues that they found offensive for far less personal reasons. For example, students successfully removed a painting of William Shakespeare from Fisher-Bennett Hall because they argued a white man should not be the face of the English department.

This conflict is not about money or logistics; it is about the hypocrisy and neglect from Penn’s administration. As a Cuban student at Penn, every time I step into La Casa Latina, I come face to face with the image of the man responsible for the death of my people, including members of my own family. The fact that CAUSA’s efforts have reached a stalemate with Penn’s executives is not only disappointing but indicative of the broader lack of empathy and effort from the institution. After 23 years of empty promises, I have doubts that Penn will ever genuinely support the Cuban students on campus — or, for that matter, sincerely condemn Che.

The persistent failure to remove Che from the mural is not just a reflection of administrative inefficiency; it is a profound neglect of basic human empathy. It is time for Penn to acknowledge that this is not merely a debate about art or politics, but about real pain, real loss, and real suffering that they’re choosing to selectively ignore.

Jennifer Mesa is a junior in the College studying Political Science and History from Miami, FL. Jennifer is also the Editor in Chief for The Pennsylvania Post. Her email is jenmesa@sas.upenn.edu.