Our growing tolerance for violence threatens to trap society in an unbreakable cycle of hostility.

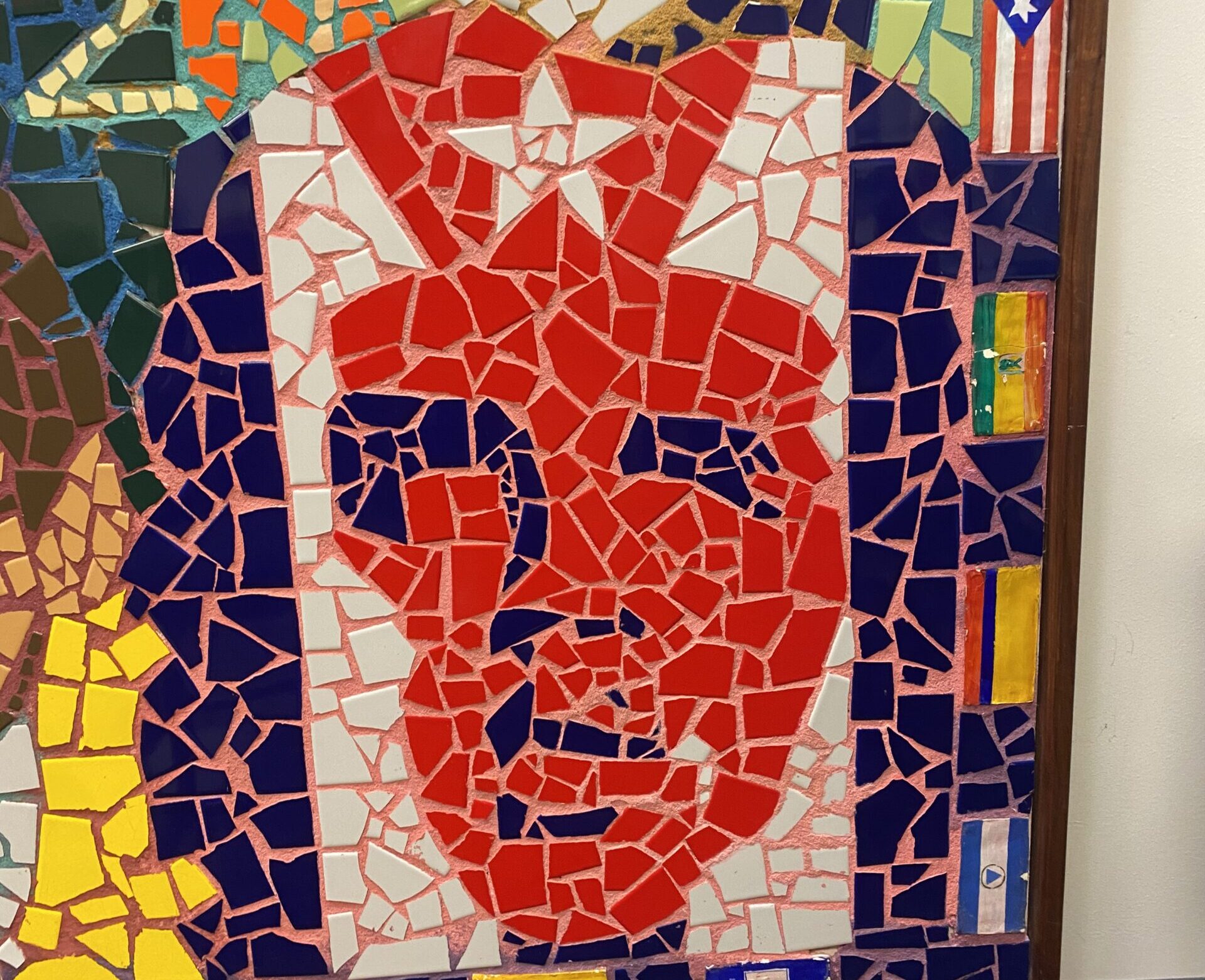

Photo Credit: Jennifer Mesa, Democracy Fund Voter Study Group

By: Seth Cyr

Violence and crime are by no means new to Philadelphia or the United States. It is something with which our media is filled, that our culture often glorifies, and upon which Hollywood and the music industry capitalize. For some, it is an art form in which they can express the innate desire of anger, wrath, or justice. For others, it is a tactic used to grab the immediate attention of the viewer; the more graphic and detailed it is, the greater an impression it leaves on the audience.

Regardless of perspective, contemporary violent culture is one that we often fail to see firsthand, existing only within the boundaries of our phones, computers, or television screens. We are distanced and disconnected from the fight scenes in movies, the clips of war footage on the news, or the evidence photos in our ever-so-popular true crime documentaries. It is something with which our society–and perhaps even our human nature–has a morbid curiosity and obsession.

Unfortunately, this disconnect fails to stop the real-world support for violence, especially in the political arena. Penn faculty and students alike have been noted for their support for the assassinations of former United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson (allegedly carried out by Penn alumnus Luigi Mangione) and conservative commentator Charlie Kirk. These messages of support originate from apps like Sidechat, where the mask of anonymity often results in more bold proclamations of support, and even extend to public accounts on TikTok. Others, while not supporting violence, make sure to use the opportunity to express their political beliefs or to make light of or mock the dark situations.

While the voices of isolated amounts of Penn students should not concern the entire university, this changes when dozens of students upvote these vile messages or when faculty publicly express their own enjoyment. For an institution that will undoubtedly produce future world leaders, this should immediately set off red flags. If these statements are held publicly, one can only imagine what these opinions are behind closed doors or in the minds of Penn faculty or students.

It seems this year, especially, that physical violence on and around campus is a recurring issue. As a whole, Philadelphia is well-above the national average in crime. While most crimes, especially robbery and homicide, are down, there have been increases in other violent crimes. Aggravated assault with a firearm and rape have seen a 28.53% and 16.36% increase from last year, respectively. Regarding Penn, while there have always been isolated cases of muggings or assaults, many were exposed to a seemingly new kind of PSA this semester. On September 25th, the Division of Public Safety sent out an email warning students to remain vigilant due to “social media trends.” These alleged trends involved the unprovoked assaults of students and residents, where they would be struck in the head by one or more individuals. One person was held at gunpoint.

Yet again, Penn students were subject to more news from the same area of and adjacent to 40th and Market Street. On Homecoming (November 8th), several hundred youths gathered, leading to numerous fights, three arrests, and injuries among youths and law enforcement alike. Motorized police sped through and around campus in high numbers, immediately signifying to observers the scale of the event. Just three days later, on November 11th, a man was shot on 40th and Walnut following a ‘verbal argument’ with another person outside of Cinemark. While no one died, it shows the ever-growing problems with this side of campus. In fact, during the draft phase of this article, another gathering of several hundred youths occurred once again at 40th and Market. Yet again, it spiraled into several fights and the injuries of some police officers.

So why do I mention these incidents? I firmly believe that violence in all forms is despicable. While it can be justified, such as when used in self-defense or in times of necessary conflict, we should never excuse it when it is used against our political opponents or innocent bystanders. Likewise, we should never glorify it in our media, lest we see the results of such societal glorification in the behavior and crime on or off college campuses. If we can justify violence against those with whom we disagree, then it becomes much easier to justify it in its other forms. We must recognize it for what it is: something that only sets us back from true progress.

It is fair to say that within a large urban center, there will be greater instances of crime and violence. However, when these problems are common within the same consistent areas or of growing intensities, there is a societal problem. When one in three US college students believes that political violence is justified to stop a speaker of an opposing political viewpoint, there is a societal problem. When ‘family-friendly’ gatherings turn into fights and the destruction of property, there is a societal problem. When college campuses find themselves victim to violent ‘social media trends’, there is a societal problem. We can argue that we actively discourage the use of violence in our schools, community organizations, or government messaging. If we see these issues continuing to manifest, it is not the tools in which the excuse of violence is tolerated, but it is in the society and culture. When a society begins to excuse violence, it will beget more violence, which in turn will beget more.

While national violent crime trends are broadly on the decline, we must ask ourselves if our nation is capable of continuing this trend. Yes, the opinions of college students do not represent actual attempts at violence, or localized crimes around Philadelphia, the broader nation. But if our society and culture continues to find itself on the path of excusing violence of any kind or engaging in political violence, we must ask whether this will change. Political violence is inherently explosive: one side will be aggrieved. It will undoubtedly initiate a chain reaction of vengeance; the question is whether this reaction will end in yet another act of violence. It is easy, then, to see how political violence is merely the start of a continual cycle, which can enable broader justifications for other forms of violence. If our society wants to avoid the worst-case scenario, change is not going to be made in schools or PSAs alone; it will be made in households. It takes a society to determine its values, and societal effort to uphold them.

Seth Cyr is a sophomore in the College studying Political Science from Gillette, Wyoming. He is an opinion writer for the Penn Post. His email is scyr@sas.upenn.edu.