Commentary can be offensive without being illegitimate.

Photo credits: Scheerpost / Mr. Fish, Instagram / @uofpenn, Design by Lexi Boccuzzi.

By Morgan Zinn

On February 4th, Penn President J. Larry Jameson issued a statement to address political cartoons published by Dwayne Booth, an artist and lecturer at the Annenberg School for Communication. Jameson condemned the cartoons as “reprehensible” and containing “antisemitic symbols” before offering the Penn community guidance on civil discourse. His comments on the importance of academic freedom and open expression, set up by frustratingly vague criticism of the cartoons, do far more to corrode those cherished values of higher education than to nurture them.

President Jameson did not mention any specific cartoons in his statement, so it’s not certain what he deemed antisemitic. Of Booth’s diverse portfolio, three cartoons contain direct references to the Holocaust and one allegedly to blood libel, an antisemitic trope. “Never Again and Again and Again,” accompanied by a column from Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Chris Hedges, depicts Holocaust survivors protesting Israel’s attacks on Gaza. Some hold signs reading, for example, “Stop the Holocaust in Gaza” and “Gaza Is the World’s Biggest Concentration Camp.”

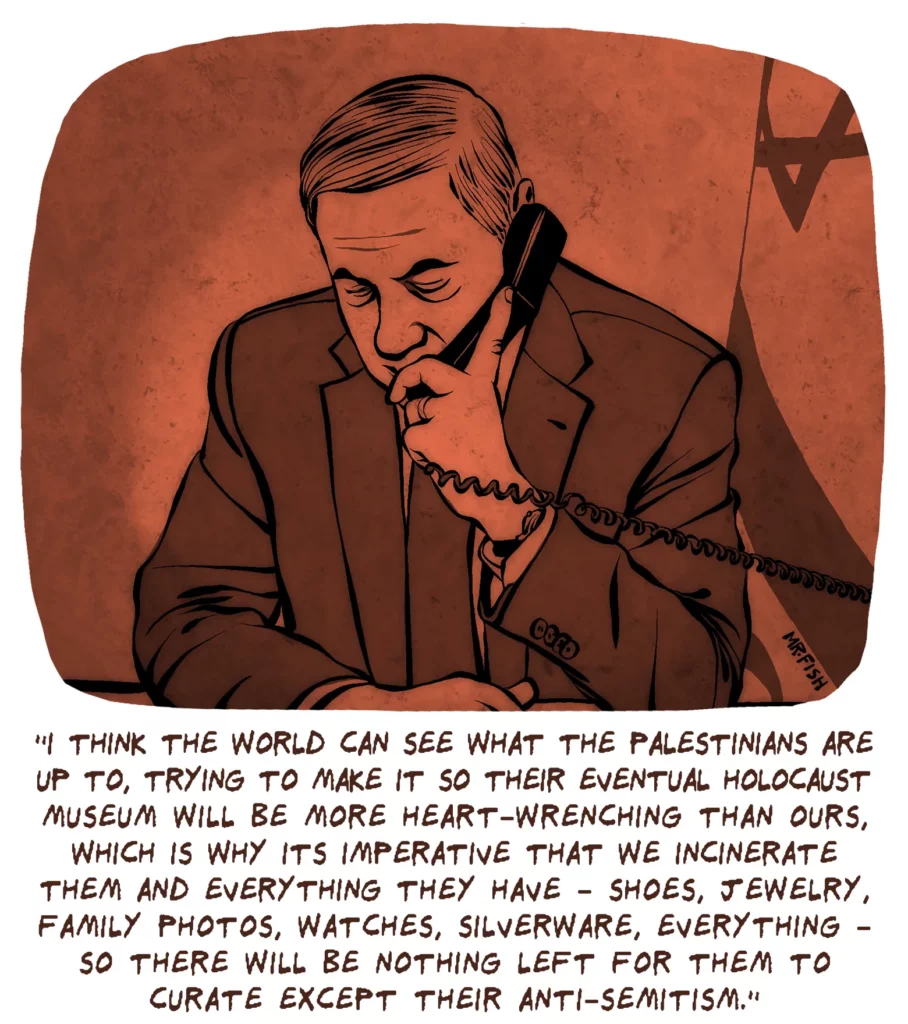

Meanwhile, “Never Again (The Sequel)” depicts, presumably, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu wearing a tactical vest. He stands above a block of text that describes a lesson he gleaned from the Holocaust: a major military power can exterminate an entire population while the world watches idly. Within the cartoon, Netanyahu now applies that lesson to Gaza. Finally, “The Shooting Gallery” depicts Netanyahu justifying the erasure of Gazan life and culture because Gazans just want a “more heart-wrenching” Holocaust museum.

Are these cartoons crass? Completely devoid of subtlety? Probably. Commentary on an ongoing “plausible genocide” demands crude heavy-handedness. Specifically, Booth highlights the irony of a state once a refuge for Holocaust survivors on its way to murdering thousands of civilians and internally displacing at least 1.7 million. While some say this minimizes the significance of the Holocaust, Booth establishes the Holocaust as a point of reference to underscore the significance of the attacks on Gaza, not to minimize it. After all, the publication of these cartoons was published with the backdrop of Israel’s assault on Gaza, one of the most destructive offensives in history, which has caused more damage in 2 months than Syria’s Aleppo faced in 4 years of war.

These cartoons may cause discomfort or feel insensitive, but that subjective perception does not mean the media contains some objective “reprehensible” quality that removes it from serious engagement. Media addressing catastrophic, man-made humanitarian crises that have been brewing for years tends to be difficult to swallow.

“The Anti-Semite,” another of Booth’s cartoons depicts American and Israeli men drinking from glasses of Gazan blood while deriding a dove holding an olive branch as a “lousy Anti-Semite.” The cartoon has been accused of referencing blood libel, an antisemitic trope dating back a millennium that has been deployed to demonize Jewish people throughout history. According to the Holocaust Encyclopedia, this term refers to the use of children’s blood for ritual purposes and baking matzah with ritual murder central to the imagery associated with this propaganda. “The Anti-Semite” contains none of those elements. Sure, the cartoon does include blood but notably lacks the ritualistic motifs commonly associated with blood libel or imagery unambiguously connected to Judaism. There is an Israeli flag, but Booth secularizes that explicitly “Jewish” ethno-religious iconography by including the American flag, underscoring its association with Israel the nation-state not with the Jewish faith.

Some may say the two cannot be separated, but, at the very least, Booth clearly attempts to do so. To ignore the artist’s decisions which represent that attempt would be to disingenuously interpret the art. If Booth had included imagery specific to Judaism or included antisemitic motifs, claims that it was referencing the blood libel trope would have some foundation. Instead, Booth likely uses the “drinking the blood of my enemies” trope. This idea is associated with popular depictions of medieval rulers like Vlad the Impaler, is referenced on wine glasses available on Amazon, and even gives a rum-based cocktail its name.

These cartoons are undoubtedly the ones that Jameson is referencing, yet Jameson’s characterization of their contents fall short of their academic, artistic, and satirical value. From atop the highest seat at Penn, Jameson delivered a reductive yet vague edict on the nature of these cartoons. In doing so, he appointed himself the sole arbiter of the views and opinions of Penn’s community.

Immediately, Jameson separated these cartoons from any academic context at Penn, stating they were “posted on a personal website [and] were not taught in the classroom.” He claimed the cartoons do not reflect the views of the University—as if Penn has some discrete, static set of opinions that can be reflected by singular pieces of media. He justifies this separation by attaching language and connotations to the cartoons that render them indefensible, calling them “reprehensible, with antisemitic symbols, and incongruent with our efforts to fight hate.” Such a strongly worded conclusion demands an equally strong argument, yet Jameson provides no logical foundation for his claims. Using his position of power as a mouthpiece, Jameson essentially removes these cartoons from honest discussion, bestowing a seemingly objective, universal truth unto the Penn community.

Meanwhile, Jameson tepidly reminds us that members of our community are allowed to express their views, “however loathsome we find them.” While it is unclear whether Jameson intends the antecedent of them to be “members” or “views,” his language quite literally creates an Us and a Them. Us, representing some abstract, essentialist idea of Penn’s views, retains its supposed ideological purity while Them, representing Booth and his cartoons, stands opposite as the object of loathing. Such a reductive dichotomy created by a leader with such power not only disrespects the intellectual diversity among the Penn community but also discourages authentic academic discourse by providing an institutionally “correct” answer to questions that have hardly been asked yet.

In his final paragraph, Jameson urges us to act with judgment and respect for our fellow Quakers, championing the strengthened safety of our learning environments. According to The Daily Pennsylvanian, however, both Booth and his family received death threats following Jameson’s statement (the cartoons themselves had been published for weeks if not months at the time). The most problematic political cartoonist in the world couldn’t lay bare an irony as rich as that.

President Jameson closed his statement with a demand that we more respectfully engage with each other in civil discourse. I wholeheartedly agree. We must resist the urge to remove media and content, no matter how loathsome we might find the ideas expressed within, from honest analysis and discussion with outright condemnations rife with moralizing language. We must respect members of our community and avoid positioning some in opposition to the whole, especially if we happen to wield the international authority and credibility of a sitting Ivy League University president, to cultivate and maintain a diversity of ideas. We must arrive at our own conclusions about the world, amongst each other, instead of allowing and inviting some institutional authority to decide these truths for us.

Perhaps well-intentioned, President Jameson’s statement and its attitudes act against the cultivation of respectful academic discourse at Penn. He delivered a damning appraisal of the work of one of Penn’s faculty, relying on his institutional authority for credibility instead of some logical deduction critical for civil discourse. In doing so, he discouraged us from arriving at our own conclusions and even exposed a Penn professor to death threats. Instead of encouraging values of mutual respect and civil discourse, statements like these, at best, offer empty platitudes and disingenuous commitments to do better or, at worst, erode a culture of free academic expression and discourage us from thinking on our own.

Morgan Zinn is a senior in the College studying Neuroscience from Baltimore, MD. Morgan is also the Layout and Design editor for The Pennsylvania Post. His email is zinn@sas.upenn.edu.