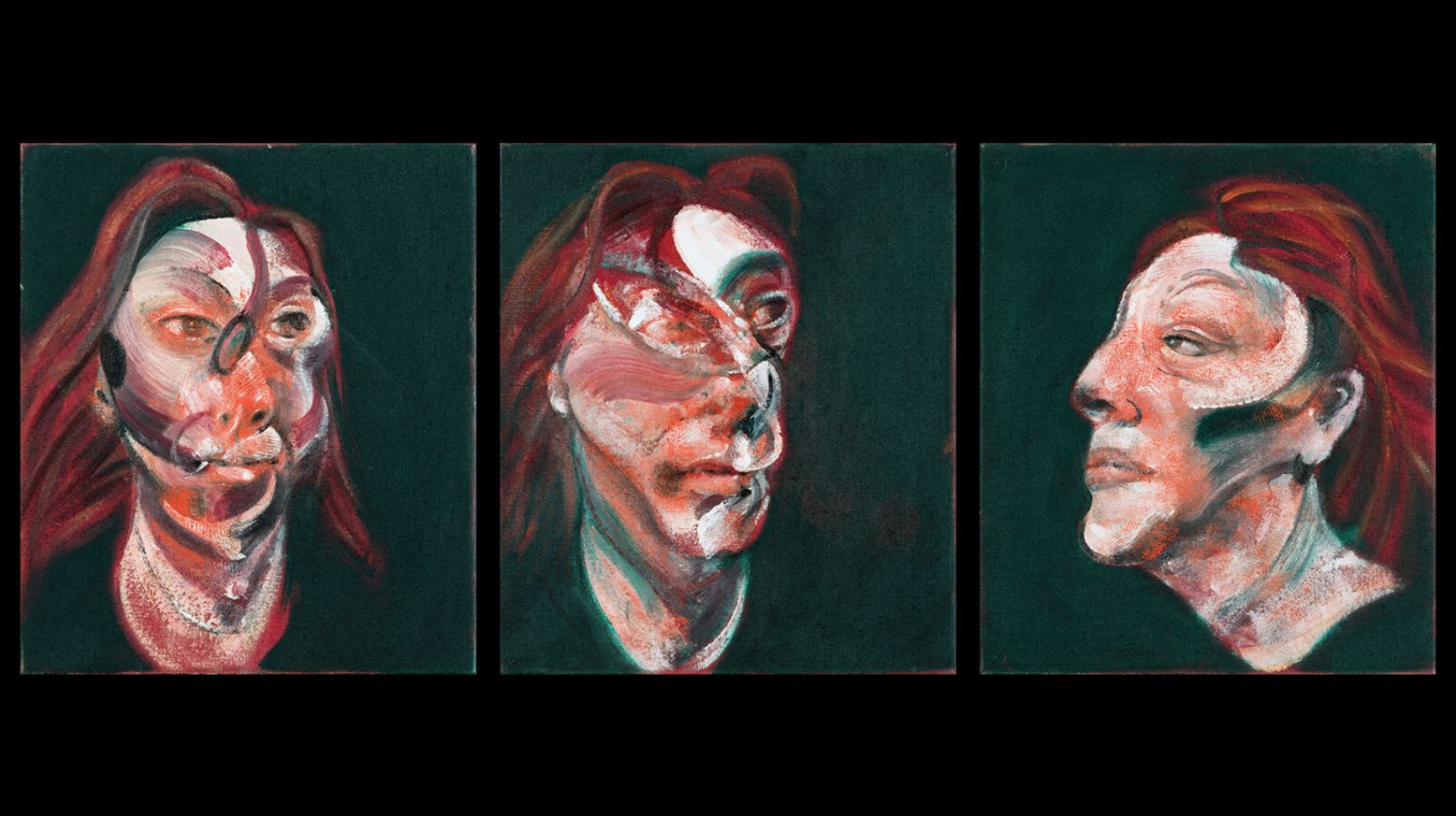

Francis Bacon’s haunting portraits capture the raw intensity of life and death, as explored in the National Portrait Gallery’s latest exhibition.

Photo Credit: Three Studies for a Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne (1965) by Francis Bacon. The Estate of Francis Bacon. All Rights Reserved, DACS/ARTIMAGE 2024. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates.

By Samuel Gilbert

The National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition on Francis Bacon was well timed. As the Christmas market spreads its log-cabined claws over Trafalgar Square, its aggressively marketed seven-pound hot chocolates and wood engraving stalls starkly contrast with the looming silhouette of the 200 year-old National Gallery. For Britons, their first and often only visit will come through an obligatory school trip to London, squeezed in-between a performance at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre and a walk past Buckingham Palace. They often miss the building just behind the National Gallery, in which some of the world’s most important portraits reside, a fine flag post for the beginning of London’s West End.

For the rest however, who do stray from that strange metaphysical field created between Britain’s most important art institution, and its most expensive hot chocolate, the NPG’s new exhibition on Francis Bacon—a dominant and subversive figure in the history of British portraiture—offers a brief but meaningful escape into his twisted post-war world of existentialism, sexuality, fragility and reflections on modern times; concerns which any winter season always draws to the front of a Londoner’s mind.

Bacon, born in Dublin in 1909 to an upper class family, found in the jazz clubs and drinking dens of Soho the friends and lovers who would become his most meaningful muses. Throughout the exhibition, Bacon’s passion for putting across ‘all the pulsations of a person’ slowly tells an ecstatically beautiful and tragic story of love, fixation, regret and catharsis.

If life is defined by relationships, then life in London is transient. Friends are made quickly over lunch breaks and coffees, and are often lost just as easily in the relentless cycle of commuting, deadlines, and never getting enough Vitamin D. The boundaries that separate colleagues and commuters from friends and partners can feel insurmountable. It is the corresponding loneliness and the inability to reach through social spaces to share passions and fears that forms the core of Bacon’s collection.

A series of men in suits, visibly ‘caged’ by Weber’s modernity, scream blindly outwards into the darkness that surrounds them. As visitors circle their paintings in the exhibition’s first room, they are as powerless to bridge that space and engage with Bacon’s subjects as they are to make themselves heard in this bleak midwinter. Bacon was often confused at critics who spoke to violence in his work, claiming that “my painting is not violent, it’s life that is violent.” This delineation is critical when understanding Bacon’s portraiture. He had no interest in illustrating, commending, or condemning. Instead he reduced his subjects to their most spartan components, revealing people as they are as opposed to how they wished to be seen.

That desire to pierce the veil between people matures in the exhibition’s final room, which is dedicated to Bacon’s friends and lovers. Here, his homosexuality flourishes as he gives a sharply intimate recount of a love that spanned three decades. George Dyer, his life partner and most painted subject, dominates the room. Best captured by Bacon on his bicycle, with the silhouette of his spectacled face gazing forwards, while his shadowed and blurred face glares outwards towards the gallery. The bicycle beneath him twists in motion, rocking in space. It is uncertain whether anything in this painting will be able to carry on beyond the moment it has been captured; though there is a painfully desperate will from Bacon for his love to keep steady, despite Dyer’s dark, brooding eye.

The central piece of the room reveals the tragedy that defined Bacon’s life and art, the fatal overdose of Dyer in 1971. It is the only piece in the gallery with a space to sit, and if you do, you see yourself slightly in the painting’s protective glass. Within that, a three panelled recollection of Dyer’s death. A naked and twisted form squats over a toilet bowl, before writhing under a dim lightbulb strung within the door frame, and then dark blood frothing from his blurred figure into a faucet on the floor. His eye clear, but closed, while the rest of Dyer comes undone in spirals of grey flesh and the darkness in the room.

Finally, the fragility and existentialism that has haunted Bacon’s life is terrifyingly realised. The looming darkness that surrounded those screaming men now descends upon the love of his life, and Bacon is powerless to reach through that door frame and do anything. The bicycle has tipped over, and Dyer has been consumed by the darkness within him.

Leaving the exhibition, back out into the cold night and the winding river of people moving from Trafalgar square. A walk towards the bright lights of the West End’s clubs, theatres and casinos makes you wonder if you might have walked into one more room of the NPG. People move along in ones, or twos, and move quickly. All aware that they will one day find themselves taking the tube for the last time after one final West End winter night.

In this truth, which Bacon couldn’t ignore, he saw an opportunity to reveal in the portraits of his subjects the beauty and terror concealed within the screens we maintain to hide ourselves. He was a master of the brush stroke, and obsessed over the fragility of life. But this never strayed into futility, and he did not have the monopoly on this obligation to reach through to people and make them heard. London is lonely, and life here is fleeting, but on these long, cold nights, we can all try to make things better for the people around us.

Samuel Elijah Gilbert is a Senior studying History at Queen Mary University of London from London, England. Samuel was an exchange student at Penn last semester. His email is samgilbert42@outlook.com.